| Clothing worn by priests in the ancient Hebrew temple was part of an over-all architecture that engaged strict functions.

Like clothing, architecture’s most basic function is to serve as covering and shelter for the body, and clothing in the ancient temple further contributed to the holiness that was crucial to the sacred place. Clothing indicated the authority of the priest and contributed to his functional role. “Holy” comes from the Old English hālig, which means “uninjured, sound, healthy, entire, complete.” The bible records that Moses declared “the world also shall be stable, that it be not moved” because of “the beauty of the holiness” of the Lord. (1 Chron. 16:29-30)

|

|

Manifestation of Holiness

When his leadership was challenged, Moses declared that the Lord chooses who is righteous by establishing a closer proximity with that person: “Even to morrow the Lord will shew who are his, and who is holy; and will cause him to come near unto him: even him whom he hath chosen… the man whom the Lord doth chose, he shall be holy.”(Num16:5) Holiness is a state of stability and health, but also of nearness to God- literal physical nearness.

“Sacred” comes from the Latin word sacrum, which refers to anything that is set apart and in God’s power. “It was generally conceived spatially, as referring to the area around a temple.” Sacredness then is the space between God and man. It is a form that is determined by the function of holiness.

To maintain a division from profane actions and purifying rituals, only certain people could enter the temple. Just before Moses received the ten tablets of commandments, Moses and the head priests were commanded to “worship at a distance.” Only Moses could approach the holy ground on the mountain. As worship progressed and more covenants were made and greater altars built, even still a cloud covered the mountain as Moses conversed with God, obscuring the place from the eyes of others.

Priests weren’t allowed to even approach the temple without appropriate clothing on and proper grooming. The strictness of the clothing was required for the priests “that they bear not iniquity and die.” The clothing worn at the temple acted as a physical manifestation of the holiness required to make the temple sacred. It showed that they belonged there.

Nadab and Abihu were consumed with fire for attempting to offer burnt sacrifices without the priesthood authority (Lev. 10:12). Only certain people could perform the rituals, and only at certain times. Even putting on the clothes followed a strict etiquette. After being washed, the high priest was dressed in this order: tunic, robe, ephod, breastplate, girlde, mitre, crown. He then was anointed, and the other priests went through the same ritual.

Clothing Mirrors Temple Design

The appearance of the priests’ clothing mirrored the temple. The design for the priestly vestige precisely outlined the temple design. The dimensions, colors, and elements were the same. It is also important to note that this clothing was created immediately after the construction of the temple. After the temple was anointed as a sacred place, the priests were immediately anointed in their vestige.

Much like the form of the temple indicates its functional role in the religion, government, and society, the clothes of the priests indicated their particular functional roles. They also were intended “for honor and beauty” of the place. Each priest had their clothing custom made to fit the proportions of their body. The clothing therefore was a vital link between each individual and the form of the temple.

When any clothing became so dirty that it couldn’t be washed back to complete purity, the clothing was disposed of by shredding and burning with the candles of the temple’s menorah. The exception to this method of disposal was the high priest’s clothing which was hidden in a secret place never to be used again.

Description of Priestly Garments

Ephod – Scholars believe the ephod began as a simple linen cloth and turned into an extravagant device for ceremony. The first ephod in Moses’ time may have been simple plain cloth. The ephod was a linen skirt that went up and over the shoulders like an apron, with open sides that were fastened with a girdle. Some scholars say the elaborate ephod of later times was designed to mirror the temple: Ephod – Scholars believe the ephod began as a simple linen cloth and turned into an extravagant device for ceremony. The first ephod in Moses’ time may have been simple plain cloth. The ephod was a linen skirt that went up and over the shoulders like an apron, with open sides that were fastened with a girdle. Some scholars say the elaborate ephod of later times was designed to mirror the temple:

It was woven of blue, purple, scarlet, and gold thread into fine linen. Gold rings on the shoulders attached straps which held the breastplate with gold chains. Two green heliodor or copper carbonate gems in gold settings on these shoulder straps had the names of each tribe of Israel inscribed on them, six on each stone. These were called “remembrance stones.” Breastplate – The Urim and Thummim was carried by the breastplate, so that it would be upon Aaron’s heart. On the breastplate “of judgment” also were four rows of three stones, certain gems that also had the names of each tribe written on them. The colors of these stones coordinated with representative colors of each tribe. Two rings with blue linen attached the breastplate on the bottom to the girdle. It was also woven of gold, of blue, and purple, and scarlet into fine linen. These jewels had special significant by denoting the authority of the wearer, “for a memorial before the LORD continually,” that Aaron “shall bear the judgment of the children of Israel upon his heart.” Robes – The robe was woven of seamless blue cloth. Pomegranates of blue, purple, and scarlet and gold bells alternate around the bottom hem of the robe. They presumably have symbolic significance- the pomegranate is the fruit of the land that God gave to the people (Deut. 8: 8). The bells ring with any movement to let everyone know the wearer’s presence; thus it was a device to help Aaron “minister.” The sound of ringing bells was also a requirement for anyone who enters the temple, “that he die not.” Mitre – Though today the mitre in the orthodox Christian church is large and pointed, the Hebrews used a simple flat turban. The mitre evolved concurrently with the rooftop and window forms of cathedrals in the middle ages, becoming larger and more triangular as the roof of the cathedral became more pitched. Though mitres of recent orthodox churches are gold or white, the Hebrew mitre was blue. As a clear indication that the function of the wearer created the sacred space, a gold plaque on the mitre read: “Holy to the Lord.” Any iniquity committed in that space bore upon the wearer. A head-tire held the mitre on the head, a cord tight around the top of the head. The lower priests mitres were similar to the high priests’ except they were easily placed on the head. Tunic – The tunic could be seen extending lower than the robe. It was checkered to match the gridded pattern of the breastplate. Girdle – The girdle around the waist completed the dress of the highest priest in the temple. The girdle was woven of sky-blue, dark-red and crimson dyed wools, and twisted linen. Josephus recorded that it was thin, very long, embroidered, and woven of colored wool and white linen. The girdles of the lower priests were probably simple plain white linen. The placement of the knot was in the front and the ends of the knot hung low, according to Josephus (Antiquities 3:7:2). Crown> – The gold plaque on the mitre is called a crown or diadem. A diadem is an “embroidered white silk ribbon, ending in a knot and two fringed strips often placed on the shoulders.” In early times it was worn about the shoulders or neck to denote rank or official and was often presented to winning athletes. The diadem is the first crown in history, dating back to Sumerian and Egyptian times. Josephus described three gold bands on a blue cap above the mitre, with finely woven linen on each band, an apparent predecessor to the kingly crown we think of today. Blue cords around the back of the head held the gold plaque in place. Trousers – Aaron’s sons who worked in the temple wore trousers “to cover the flesh of their nakedness.” They were pure 6-ply white flax and simply woven. Other Lower Priest Clothing – Aaron’s sons who worked in the temple wore tunics, girldes, and less formal head-coverings. Each article was pure white. On the day of atonement, the High Priest wore clothing similar to the ordinary priests. He wore two tunics (one in the morning and one in the evening), trousers “upon his flesh,” a girdle, and a mitre. But afterward these clothes were to never be worn again. The priest “shall take off the linen garments, which he put on when he went into the holy place, and he shall leave them there.” They are all pure white simply-woven flax, unlike the usual colorful dress. Urim and Thummim – The Urim and Thummim, traditionally translated to mean “light and perfection,” was an oracle worn on the High Priest’s breastplate through which he received answers from God. Some speculate that the secret name of God was written on paper and inserted next to the device and that is how it got its holiness in order to answer important questions. Others speculate that it was a device, or two, that was placed in a pocket and pulled out with an answer. Writing seems to be importantly involved. Some speculate that Urim and Thummim translates to “cursed or innocent” and that it was a tool of judgment. In 1 Samuel 14:41, Saul discovered the sinner in a group by continually splitting the group into subgroups while asking for “Urim” or “Thummim” which group contains the culprit. This suggests that the Urim and Thummim used cleromancy because this verse in the Septuagint version indicates the object was manipulated to divine the answer. Also, the next verse says they “cast lots.” Because all but two recorded uses of the device brought yes or no answers, some scholars believe it produced single words. Talmudic rabbis traditionally taught that light shined from the gems on the breastplate to create letters that spelled out an answer. Josephus said it shined brilliantly. Some even said the gems moved (See Yoma 73). The Urim and Thummim was believed to have been created by God and given to Moses. It was used for matters that concerned the entire congregation. Extensive research has determined that the Urim and Thummim had a significant role in ancient Israel for receiving revelation from God. |

Original Garments Given To Adam

According to rabbinic literature, Adam’s original body reached from earth to heaven, and was “of extreme beauty and sunlike brightness.” His “skin was a bright garment.” He didn’t have robes of skin, but garments of light (Gen. R. xx.), which he needed in order to remain in the Garden of Eden.

The garment of light was lost upon Adam’s fall and they sewed aprons with fig leaves when they discovered that they were naked. God created garments of skins for them. Some claim these garments were made during the sixth day of creation.

Mythological Judaism further claims that Adam reclaimed a garment of light when he repented of his sin, a garment which the Messiah also wears.

Patriarchal Authority

Adam’s descendants handed down these garments of skin patriarchally, according to some Jewish literature. They were handed down to the eldest son, carried in Noah’s ark, and eventually stolen by the evil king Nimrod. Before he was defeated, the garments caused people and animals to bow down to Nimrod. Jacob stole the garments of skin from Esau in order to get his father’s blessing.

Clothing showed proof of leadership in ancient times. Joseph’s multi-colored coat is another example of patriarchal blessing in the form of clothing. It is there for all to see, part of a person’s image, and it is given to the wearer as a token of their authority. The clothes of the king was considered an honor given by the people, a glory given by God. The clothing of the temple priest therefore must indicate the glory and authority given by God and the people.

Other Ancient Cultures

The the Hebrew sacred temple clothing had influence from other cultures of that time, including Egypt and Assyria. Clothing specific to the Hebrews can be seen in later cultures, particularly in Crusaders and the early Christian church. There are startling similarities to sacred clothing in the Far East and Americas.

Idols and divination

Some scholars say that a new kind of graven image or idol had its origins in the ephod clothing. Gideon and Micah created a golden ephod that was worshiped by Israel (Judges 8:27). As an indicator of authority, the gold ephod of Micah was no longer worn on the body, but become an object unto itself like a statue. Micah’s ephod was known as a Teraphim, or manifest object. Such an ephod became known as pesel or massekah, meaning “graven image” and “molten image.” As the ephod became used more and more as an object to be carried rather than worn, the word Ephod became known to mean idol.

People began to think the jewels on the ephod and breastplate themselves were the Urim and Thummim. Since it was regarded as an object of divination, the jewels began to be considered as giving the ability to tell the future.

Perhaps another clue to the function of the Urim and Thummim, later divinations involved looking into the gems. One would look into the jewels and derive an answer from how light would shine back. This practice spread to the pagan looking glass, mirror, crystal ball, or water basin. Cleromancy was often involved. Islamists combined it with the ancient practice of “pulling straws.” They would pull a barren arrow shaft from a container of shafts and read the answer written on it: yes, no, or blank. Pagans ritually divined from bones or sticks.

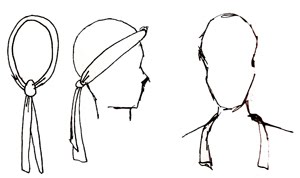

The golden diadem can be traced back to Egypt. The diadem had a gold band around the head, with an insignia on the front and two strands hanging from the back. As part of this dressing, gold bands were worn about the shoulders or neck to denote rank or official. It can perhaps be seen in the most authoritative Greek alpha letter alpha Ω.

Rabbi Elieze claimed the priestly crown of the Hebrews was displayed in Rome after Israel was conquered by the Romans, which would explain how the temple crown came to be resembled by kingly crowns of Rome and Europe. The gold crown of Charlemagne derives from the ancient Hebrew mitre, and replaces the gold plate the gems of the breastplate.

The crown eventually became a metal hat, a combination of the diadem and mitre. Ancient Celts were perhaps the first to wear a gold plate as a crown, called a mime.

The crown eventually became a metal hat, a combination of the diadem and mitre. Ancient Celts were perhaps the first to wear a gold plate as a crown, called a mime.

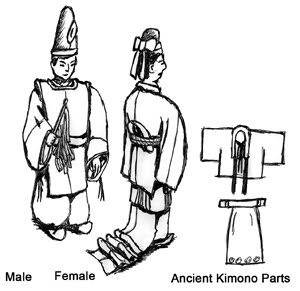

Religious clothing in ancient Egypt included an apron that resembled the ephod. Like many other cultures Egypts religious clothing was different for men and women. The men’s ephod consisted of several colorful layers of phallic shaped aprons with a large knot for the girdle above. The female’s consisted of a simple belt with a knotted girdle.

Tunics were worn beneath. The miter was also different for the male and female, with a veil coming down over the sides of the female’s.

Each wore a shawl over the shoulders, a sort of robe. A bowed knot bound it in front of the heart. This bears great similarity to the Japanese kimono in the Shinto culture. The Greek robe is well known as the one-shouldered toga. The robe also goes over only one shoulder in many Hindu and Shinto cases.

Each wore a shawl over the shoulders, a sort of robe. A bowed knot bound it in front of the heart. This bears great similarity to the Japanese kimono in the Shinto culture. The Greek robe is well known as the one-shouldered toga. The robe also goes over only one shoulder in many Hindu and Shinto cases.

The crusading knights also adopted many elements of the Hebrew temple clothes. The graduation robes of today include many similarities, including the cut and tassles on the sleeves, and the tassle on the peculiar hat.

Shinto, Hinduism, Buddhism

The Zen Buddhist uses a rectangular apron that resembles the ephod. He also has a robe that goes over one shoulder. The Hindu priest uses the same kind of robe, a turban with an insignia on the front, and also a necklace much like the ancient Egyptian.

The Shinto priest in Japan distinguishes the male and female clothing like the Egyptians. Both wore baggy trousers with a tunic, robe, and sash on top. The female robe was sometimes pleated. Each wore an apron resembling the ephod.

The male mitre resembles the Egyptian with a rim on the bottom and an insignia in front. The female mitre is a simple band with a bow in the back, like the diadem. The female tunic extended from the back much like the wedding dresses we see today.

In the ancient Japanese shrine Ise-jingu and many other shrines, all of the priests had white robes. Shinto priests had fringes on the ends of their sleeves much like the tassels in Hebrew robes.

The martial artist wears a headband with the name of his clan written on the front, and a knot in the back with two ends falling down. This is a perfect similarity to the diadem of the ancient Middle East.

|

|

Native America

Mayan priests are often portrayed in sculptures with long patterned robes with frills at the bottom. They also wore sandals and wrist-bands much like the Egyptian, Assyrian, and Hebrew priest. A thick necklace denotes authority. The hat bears striking resemblance to the Hebrew mitre. The Mayan priest had a long cord falling from the back of the head, like the diadem. Notice also in that link the frilled apron with the form of a branch on it.

The same ephod can be seen with the Aztecs. The priest in that photo holds a staff like the Egyptian priest often does. The priest on the left is all in white, with a sash, ephod, and robe. The priest on the right wears a hat with an insignia on the front, jeweled cord around the rim, and a pointy top much like the Egyptian hat.

The elaborate headpiece often has long coverings over the ears like the Eygptian diadem. This ear covering is seen throughout tribes in the United States. The stereotypical Native American headpiece is a crown of feathers, a different evolution than the gemmed crown of Europe.

The first Christian priest to come to America, Diego de Landa, wrote of the similarities. The priest wore a long, solemn robe, and children ready for ritual washing would have a white cloths placed on their heads. Women sometimes wore a robe of feathers. He includes this image to the right in Yucatán before and after the conquest of Tutul Xiu, ruler of Maya.

The first Christian priest to come to America, Diego de Landa, wrote of the similarities. The priest wore a long, solemn robe, and children ready for ritual washing would have a white cloths placed on their heads. Women sometimes wore a robe of feathers. He includes this image to the right in Yucatán before and after the conquest of Tutul Xiu, ruler of Maya.

The man wears a hat almost exactly like the Egptian, Hebrew, or even Shinto mitre. He wears a necklace of authority, a sash, and wrist bands (and not much else.)

Landa describes a sash worn about the waste with a knot hanging in the front, which was skillfully embroidered. He describes “large square mantles, which they threw over the shoulders.” Here is another image by Friar Landa that shows striking resemblances.

The triangular apron is much like the Egyptian priest. The cape is checkered like the Hebrew tunic, and is tied on the chest like the Egyptian shawl. He wears a thick multi-layered necklace like the Egyptians. He wears a head-piece and sandals. The form of dress is just too similar to ignore.

Need For Sacred Clothing

The function and form of early Hebrew temple clothing reveals a different understanding of the relationship between the human body and architecture, an understanding that spread throughout the world. The need to cover and shelter the body stemmed from the loss of glorious light in the body. The beautiful garment was aesthetic for the purpose of establishing authority among the people and gifts of God. The form of the clothing echoed the form of the building and connected it to the human body. In essence, the clothing fulfilled the functional requirements of the person to establish a space appropriate for all the people.

© Benjamin Blankenbehler 2014

Images: The following are public domain or used under Fair Use Copyright Rules (in order of appearance):

“Hebrew trumpet” from Filippo Bonanni: Gabinetto Armonico (1723)

“Benito Antiquitatum Iudicarum Libri IX. In quis, praeter Iudaeae, Hierosolymorum, & Templi Salomonis accuratam delineationem, praecipui sacri ac profani gentis ritus describuntur” from Arias Montanus (1593)

See also “Temptation of Adam and Eve, Expulsion from the garden” At Brarup church in Denmark (1500)

images from Yucatán before and after the conquest” from Diego de Landa (1524-1579), Kaldari/ Kaldari on wikipedia/publi domain?

All other copyright Architecture Revived