History of Israel

Jump to navigationJump to search

| History of Israel |

|---|

|

| Prehistory |

| Ancient Israel and Judah |

| Second Temple period (530 BCE–70 CE) |

| Late Classic (70-636) |

| Middle Ages (636–1517) |

| Modern history (1517–1948) |

| State of Israel (1948–present) |

| History of the Land of Israel by topic |

| Related |

The Land of Israel, also known as the Holy Land or Palestine, is the birthplace of the Jewish people, the place where the final form of the Hebrew Bible is thought to have been compiled, and the birthplace of Judaism and Christianity. It contains sites sacred to Judaism, Samaritanism, Christianity, Islam, Druze and the Baháʼí Faith. The region has come under the sway of various empires and, as a result, has hosted a wide variety of ethnicities. The adoption of Christianity by the Roman Empire in the 4th century led to a Greco-Roman Christian majority which lasted not just until the 7th century when the area was conquered by the Arab Muslim Empires, but for another full six centuries. It gradually became predominantly Muslim after the end of the Crusader period (1099-1291), during which it was the focal point of conflict between Christianity and Islam. From the 13th century it was mainly Muslim with Arabic as the dominant language and was first part of the Syrian province of the Mamluk Sultanate and after 1516 part of the Ottoman Empire until the British conquest in 1917-18.

A Jewish national movement, Zionism, emerged in the late-19th century (partially in response to growing antisemitism), as part of which Aliyah (Jewish return from diaspora) increased. During World War I, the British government publicly committed to create a Jewish National Home and was granted a Mandate to rule Palestine by the League of Nations for this purpose. A rival Arab nationalism also claimed rights over the former Ottoman territories and sought to prevent Jewish migration into Palestine, leading to growing Arab–Jewish tensions. Israeli independence in 1948 was accompanied by an exodus of Arabs from Israel, the Arab–Israeli conflict[1] and a subsequent Jewish exodus from Arab and Muslim countries to Israel. About 43% of the world’s Jews live in Israel today, the largest Jewish community in the world.[2]

In 1979, an uneasy Egypt–Israel Peace Treaty was signed, based on the Camp David Accords. In 1993, Israel signed Oslo I Accord with the Palestine Liberation Organization, followed by establishment of the Palestinian National Authority and in 1994 Israel–Jordan peace treaty was signed. Despite efforts to finalize the peace agreement, the conflict continues to play a major role in Israeli and international political, social and economic life.

In its early decades, the economy of Israel was largely state-controlled and shaped by social democratic ideas. In the 1970s and 1980s, the economy underwent a series of free market reforms and was gradually liberalized.[3] In the past three decades, the economy has grown considerably, but GDP per capita has increased faster than the increase in wages.[4]

Periodisation

The periodisation is subject to the progress of research, to regional, national, and ideological interpretation, as well as personal preference of the individual researcher. For an overview of a mainstream periodisation system for the wider region, see List of archaeological periods (Levant). Periodisation organized by the seat of the controlling state is shown below:

Prehistory

Es Skhul cave

Between 2.6 and 0.9 million years ago, at least four episodes of hominine dispersal from Africa to the Levant are known, each culturally distinct. The oldest evidence of early humans in the territory of modern Israel, dating to 1.5 million years ago, was found in Ubeidiya near the Sea of Galilee.[5] The flint tool artefacts have been discovered at Yiron, the oldest stone tools found anywhere outside Africa. Other groups include 1.4 million years old Acheulean industry, the Bizat Ruhama group and Gesher Bnot Yaakov.[6]

In the Carmel mountain range at el-Tabun, and Es Skhul,[7] Neanderthal and early modern human remains were found, including the skeleton of a Neanderthal female, named Tabun I, which is regarded as one of the most important human fossils ever found.[8] The excavation at el-Tabun produced the longest stratigraphic record in the region, spanning 600,000 or more years of human activity,[9] from the Lower Paleolithic to the present day, representing roughly a million years of human evolution.[10] Other notable Paleolithic sites include caves Qesem and Manot. The oldest fossils of anatomically modern humans found outside Africa are the Skhul and Qafzeh hominids, who lived in northern Israel 120,000 years ago.[11] Around 10th millennium BCE, the Natufian culture existed in the area.[12]

Bronze and Iron Ages

Map of the ancient Near East

Canaanites (Bronze Age)

During the 2nd millennium BCE, Canaan, part of which later became known as Israel, was dominated by the New Kingdom of Egypt from c.1550 to c. 1180. The earliest recorded battle in history took place in 1457 BCE, at Megiddo (known in Greek as Armageddon), between Canaanite forces and those of Pharoh Thutmose III. The Canaanites left no written history, but Thutmose’s scribe, Tjaneni recorded the battle.[13]

Early Israelites (Iron Age I)

The Merneptah Stele. While alternative translations exist, the majority of biblical archeologists translate a set of hieroglyphs as “Israel,” representing the first instance of the name in the historical record.

The first record of the name Israel (as ysrỉꜣr) occurs in the Merneptah stele, erected for Egyptian Pharaoh Merneptah (son of Ramses II) c. 1209 BCE, “Israel is laid waste and his seed is not.”[14] William G. Dever sees this “Israel” in the central highlands as a cultural and probably political entity, more an ethnic group rather than an organized state.[15]

Ancestors of the Israelites may have included Semites native to Canaan and the Sea Peoples.[16] McNutt says, “It is probably safe to assume that sometime during Iron Age I a population began to identify itself as ‘Israelite'”, differentiating itself from the Canaanites through such markers as the prohibition of intermarriage, an emphasis on family history and genealogy, and religion.[17]

The archeological evidence indicates a society of village-like centres, but with more limited resources and a small population.[18] Villages had populations of up to 300 or 400,[19][20] which lived by farming and herding, and were largely self-sufficient;[21] economic interchange was prevalent.[22] Writing was known and available for recording, even in small sites.[23]

First Hebrew texts and religion

The first use of grapheme-based writing originated in the area, probably among Canaanite peoples resident in Egypt. This evolved into the Phoenician alphabet from which all modern alphabetical writing systems are descended. The Paleo-Hebrew alphabet was one of the first to develop and evidence of its use exists from about 1000 BCE[24] (see the Gezer calendar), the language spoken was probably Biblical Hebrew.

Monotheism, the belief in a single all-powerful law-giving God is thought to have evolved among the Hebrew speakers gradually, over the next few centuries, from a number of separate cults,[25] leading to the first versions of the religion now known as Judaism.

Israel and Judah (Iron Age II)

City of David in Jerusalem

The Hebrew Bible describes constant warfare between the Israelites and the Philistines whose capital was Gaza. The Phillistines were Greek refugee-settlers who inhabited the southern Levantine coast.[26] The Bible states that King David founded a dynasty of kings and that his son Solomon built a temple. Both David and Solomon are widely referenced in Jewish, Christian and Islamic texts. Standard Biblical chronology suggests that around 930 BCE, following the death of Solomon, the kingdom split into a southern Kingdom of Judah and a northern Kingdom of Israel. The Bible’s Books of Kings state that soon after the split Pharoh “Shishaq” invaded the country plundering Jerusalem.[27] An inscription over a gate at Karnak in Egypt recounts such an invasion by Pharoh Sheshonq I.[28]

The archeological evidence for this period is extremely sparse, leading some scholars to suggest that this section of the Hebrew Bible, which includes texts written two centuries later, exaggerates the importance of David and Solomon.[29] The earliest references to the “House of David” have been found in two inscriptions, on the Tel Dan Stele and the Mesha Stele; the latter is a Moabite stele, now in the Louvre, which describes an 840 BCE invasion of Moab by Omri, king of Israel. Jehu, son of Omri, is referenced by Assyrian records (now in the British Museum). Modern archeological findings show that Omri’s capital city, Samaria, was large and Finkelstein has suggested that the Biblical account of David and Solomon are an attempt by later Judean rulers to ascribe Israel’s successes to their dynasty.

Assyrian invasions

In 854 BCE, according to Assyrian records (the Kurkh Monoliths)[30] an alliance between Ahab of Israel and Ben Hadad II of Aram Damascus managed to repulse the incursions of the Assyrians, with a victory at the Battle of Qarqar. This is not included in the Bible which describes conflict between Ahab and Ben Hadad.[31] Around 750 BCE, the Kingdom of Israel was destroyed by Assyrian king Tiglath-Pileser III. The Philistine kingdom was also destroyed. The Assyrians sent most of the population of the northern Israelite kingdom into exile, thus creating the “Lost Tribes of Israel“. The Samaritans claim to be descended from survivors of the Assyrian conquest. An Israelite revolt (724–722 BCE) was crushed after the siege and capture of Samaria by the Assyrian king Sargon II.[32]

Modern scholars believe that refugees from the destruction of Israel moved to Judah, massively expanding Jerusalem and leading to construction of the Siloam Tunnel during the rule of King Hezekiah (ruled 715–686 BCE).[33] The tunnel could provide water during a siege and its construction is described in the Bible.[34] A Hebrew plaque left by the construction team still exists.[35]

Sargon’s son, Sennacherib, tried and failed to conquer Judah, during Hezekiah’s reign. Assyrian records say that Sennacherib levelled 46 walled cities and besieged Jerusalem, leaving after receiving extensive tribute.[36] The Bible also refers to tribute,[37] and suggests that Hezekiah was aided by Taharqa, king of Kush (now Sudan), in repulsing the Assyrians. The Twenty-fifth Dynasty of Egypt were Nubian Pharohs and they probably defeated the Assyrians.[38] Sennacherib had a 12 meter by 5-metre frieze erected in his palace in Nineveh (now in Iraq) depicting his victory at Lachish, the second largest city in Judah.

The Bible describes a tradition of religious men (“prophets“) exercising some form of free speech and criticizing rulers. The most famous of these was Isaiah, who witnessed the Assyrian invasion and warned of its consequences.[citation needed]

Under King Josiah (ruler from 641 – 619), the book of Deuteronomy was either rediscovered or written. The Book of Joshua and the accounts of the kingship of David and Solomon in the book of Kings are believed to have the same author. The books are known as Deuteronomist and considered to be a key step in the emergence of monotheism in Judah. They emerged at a time that Assyria was weakened by the emergence of Babylon and may be a committing to text of pre-writing verbal traditions.[39]

Babylonian, Persian, and Hellenistic periods (586–37 BCE)

In 586 BCE King Nebuchadnezzar II of Babylon conquered Judah. According to the Hebrew Bible, he destroyed Solomon’s Temple and exiled the Jews to Babylon. The Phillistines were also driven into exile. The defeat of Judah was recorded by the Babylonians[40][41] (see the Babylonian Chronicles). Babylonian and Biblical sources suggest that the Judean king, Jehoiachin, switched allegiances between the Egyptians and the Babylonians and that invasion was a punishment for allying with Babylon’s principal rival, Egypt. The exiled Jews may have been restricted to the elite. Jehoiachin was eventually released by the Babylonians. Tablets which seem to describe his rations were found in the ruins of Babylon (see Jehoiachin’s Rations Tablets). According to both the Bible and the Talmud, the Judean royal family (the Davidic line) continued as head of Babylonian Jewry, called the “Rosh Galut” (head of exile). Arab and Jewish sources show that the Rosh Galut continued to exist (in what is now Iraq) for another 1,500 years, ending in the eleventh century.[42]

Obverse of Yehud silver coin

In 538 BCE, Cyrus the Great of Persia conquered Babylon and took over its empire. Cyrus issued a proclamation granting subjugated nations (including the people of Judah) religious freedom (for the original text see the Cyrus Cylinder). According to the Hebrew Bible 50,000 Judeans, led by Zerubabel, returned to Judah and rebuilt the temple. A second group of 5,000, led by Ezra and Nehemiah, returned to Judah in 456 BCE although non-Jews wrote to Cyrus to try to prevent their return. Modern scholars believe that the final Hebrew versions of the Torah and Books of Kings date from this period, that the returning Israelites adopted an Aramaic script (also known as the Ashuri alphabet), which they brought back from Babylon; this is the current Hebrew script. The Hebrew calendar closely resembles the Babylonian calendar and probably dates from this period.[43]

The Persians also conquered Egypt, posting a Judean military garrison on Elephantine Island near Aswan. In the early 20th century 175 papyrus documents were discovered, recording activity in this community, including the “Passover Papyrus”, a letter instructing the garrison on how to correctly conduct the Passover feast.[44]

In 333 BCE, the Macedonian ruler Alexander the Great defeated Persia and conquered the region. After Alexander’s death, his generals fought over the territory he had conquered and Judah became the frontier between the Seleucid Empire and Ptolemaic Egypt, eventually becoming part of the Seleucid Empire in 200 BCE at the battle of Panium (fought near Banias on the Golan Heights). The first translation of the Hebrew Bible, the Greek Septuagint was made in 3rd Century BCE Alexandria, during the rule of Ptolemy II Philadelphus, for the Library of Alexandria.

Hasmonean dynasty (140–37 BCE)

In the 2nd century BCE, Seleucid ruler Antiochus IV Epiphanes tried to eradicate Judaism in favour of Hellenistic religion. This provoked the 174–135 BCE Maccabean Revolt led by Judas Maccabeus (whose victory is celebrated in the Jewish festival of Hanukkah). The Books of the Maccabees describe the uprising and the end of Greek rule, these books were not added to the sacred Jewish canon and as a result the Hebrew originals were lost (Greek translations survived).

A Jewish party called the Hasideans opposed both Hellenism and the revolt, but eventually gave their support to the Maccabees. Modern interpretations see the initial stages of the uprising as a civil war between Hellenised and orthodox forms of Judaism.[45][46]

The Hasmonean dynasty of Jewish priest-kings ruled Judea with the Pharisees, Sadducees and Essenes as the principal Jewish social movements. As part of the struggle against Hellenistic civilization, the Pharisee leader Simeon ben Shetach established the first schools based around meeting houses.[47] This led to Rabbinical Judaism. Justice was administered by the Sanhedrin, which was a Rabbincal assembly and law court whose leader was known as the Nasi. The Nasi’s religious authority gradually superseded that of the Temple’s high priest, who under the Hasmoneans was the king himself.[48]

The Hasmoneans continually extended their control over much of the region.[49] In 125 BCE the Hasmonean ethnarch John Hyrcanus subjugated Edom and forcibly converted its population to Judaism.[50]

Hyrcanus’ son Alexander Jannaeus established good relations with the Roman Republic, however there was growing tension between Pharisees and Sadducees and a conflict over the succession to Janneus, in which the warring parties invited foreign intervention on their behalf.

Roman period (64 BCE–4th century CE)

In 64 BCE the Roman general Pompey conquered Syria and intervened in the Hasmonean civil war in Jerusalem, restoring Hyrcanus II as High Priest and making Judea a Roman vassal kingdom. During the siege of Alexandria in 47 BCE, the lives of Julius Caesar and his protégé Cleopatra were saved by 3,000 Jewish troops sent by Hyrcanus II and commanded by Antipater, whose descendants Caesar made kings of Judea.[51]

Herodian dynasty and Roman province

Portion of the Temple Scroll, one of the Dead Sea Scrolls written by the Essenes

From 37 BCE to 6 CE, the Herodian dynasty, Jewish-Roman client kings, descended from Antipater, ruled Judea. Herod the Great considerably enlarged the temple (see Herod’s Temple), making it one of the largest religious structures in the world. At this time, Jews formed as much as 10%[52] of the population of the entire Roman Empire, with large communities in North Africa and Arabia. Despite the fame of the temple, Rabbinical Judaism, led by Hillel the Elder, began to assume popular prominence over the Temple priesthood. The Romans gave the Jewish Temple in Jerusalem permission not to display an effigy of the emperor, the only religious structure in the Roman Empire that was exempt. Special dispensation was granted for Jewish citizens of the Roman Empire to pay a tax to the temple.

Augustus made Judea a Roman province in 6 CE, deposing the last Jewish king, Herod Archelaus, and appointing a Roman governor. There was a small revolt against Roman taxation led by Judas of Galilee and over the next decades tensions grew between the Greco-Roman and Judean population centered on attempts to place effigies of the Emperor Caligula in Synagogues and in the Jewish temple.[53][54]

According to the Christian scriptures, Jesus was born in the last years of Herod’s rule, probably in the Judean city of Bethlehem. Jesus is thought to have been a Galilean Jewish reformer (from Nazareth), and was executed in Jerusalem by the Roman governor Pontius Pilate between 25 and 35 CE. All his key followers, the Twelve Apostles, were Jews including Paul the Apostle (5–67 CE) who took critical steps towards creating a new religion, defining Jesus as the “Son of God”. In the year 50 CE, the Council of Jerusalem led by Paul, decided to abandon the Jewish requirement of circumcision and the Torah, creating a form of Judaism highly accessible to non-Jews and with a more universal notion of God. Another Jewish follower, Peter is believed to have become the first Pope.

In 64 CE, the Temple High Priest Joshua ben Gamla introduced a religious requirement for Jewish boys to learn to read from the age of six. Over the next few hundred years this requirement became steadily more ingrained in Jewish tradition.[55]

Jewish–Roman wars

In 66 CE, the Jews of Judea rose in revolt against Rome, naming their new state as “Israel”.[56] The events were described by the Jewish leader and historian Josephus, including the defence of Jotapata, the siege of Jerusalem (69–70 CE) and the desperate last stand at Masada under Eleazar ben Yair (72–73 CE).

The Temple and most of Jerusalem was destroyed. During the Jewish revolt, most Christians, at this time a sub-sect of Judaism, removed themselves from Judea. The rabbinical/Pharisee movement led by Yochanan ben Zakai, who opposed the Sadducee temple priesthood, made peace with Rome and survived. After the war Jews continued to be taxed in the Fiscus Judaicus, which was used to fund a temple to Jupiter. An arch commemorating the victory was erected in Rome and still exists.

Tensions and attacks on Jews around the Roman Empire led to a massive Jewish uprising against Rome from 115 to 117. Jews in Libya, Egypt, Cyprus and Mesopotamia fought against Rome. This conflict was accompanied by large-scale massacres of both sides. Cyprus was so severely depopulated that new settlers were imported and Jews banned from living there.[57]

In 131, the Emperor Hadrian renamed Jerusalem “Aelia Capitolina” and constructed a Temple of Jupiter on the site of the former Jewish temple. Jews were banned from living in Jerusalem itself (a ban that persisted until the Arab conquest), and the Roman province, until then known as Iudaea Province, was renamed Palaestina, no other revolt led to a province being renamed.[58] The names “Palestine” (in English) and “Filistin” (in Arabic) are derived from this.

From 132 to 136, the Jewish leader Simon Bar Kokhba led another major revolt against the Romans, again renaming the country “Israel”[59] (see Bar Kokhba Revolt coinage). The Bar Kochba revolt probably caused more trouble for the Romans than the better documented revolt of 70.[60] Christians refused to participate in the revolt and from this point the Jews regarded Christianity as a separate religion.[61] The revolt was eventually crushed by Emperor Hadrian himself. During the Bar Kokhba revolt a rabbinical assembly decided which books could be regarded as part of the Hebrew Bible: the Jewish apocrypha and Christian books were excluded.[62] As a result, the original text of some Hebrew texts, including the Books of Maccabees were lost (Greek translations survived).

A rabbi of this period, Simeon bar Yochai, is regarded as the author of the Zohar, the foundational text for Kabbalistic thought. However, modern scholars believe it was written in Medieval Spain.[63]

After the 136 CE Jewish defeat

After suppressing the Bar Kochba revolt, the Romans exiled the Jews of Judea, but not those of Galilee. The Romans permitted a hereditary Rabbinical Patriarch (from the House of Hillel, based in Galilee), called the “Nasi” to represent the Jews in dealings with the Romans. The most famous of these was Judah haNasi, who is credited with compiling the final version of the Mishnah (a massive body of Jewish religious texts interpreting the Bible) and with strengthening the educational demands of Judaism by requiring that illiterate Jews be treated as outcasts. As a result, many illiterate Jews may have converted to Christianity.[64] Jewish seminaries, such as those at Shefaram and Bet Shearim, continued to produce scholars. The best of these became members of the Sanhedrin,[65] which was located first at Sepphoris and later at Tiberias.[66] Before the Bar Kochba uprising, an estimated 2/3 of the population of Galilee and 1/3 of the coastal region were Jewish.[67] In the Galillee, many synagogues have been found dating from this period,[68] and the burial site of the Sanhedrin leaders was discovered in 1936.[69][70] There was a notable rivalry between Palestinian and Babylonian academies. The former thought that leaving the land in peaceful times was tantamount to idolatry and many would not ordain Babylonian students for fear they would then return to their Babylonian homeland, while Babylonian scholars thought that Palestinian rabbis were descendents of the ‘inferior stock’ putatively returning with Ezra after the Babylonian exile. An economic crisis and heavy taxation to finance the wars of imperial succession that affected the Roman empire in the 3rd century led to further Jewish migration from Syria Palaestina to the more tolerant Persian Sassanid Empire, where a prosperous Jewish community with extensive seminaries existed in the area of Babylon.[71]

Rome adopts Christianity

Early in the 4th century, the Emperor Constantine made Constantinople the capital of the East Roman Empire and made Christianity an accepted religion. His mother, Helena made a pilgrimage to Jerusalem (326–328) and led the construction of the Church of the Nativity (birthplace of Jesus in Bethlehem), the Church of the Holy Sepulchre (burial site of Jesus in Jerusalem) and other key churches that still exist. The name Jerusalem was restored to Aelia Capitolina and it became a Christian city. Jews were still banned from living in Jerusalem, but were allowed to visit and worship at the site of the ruined temple.[72] Over the course of the next century Christians worked to eradicate “paganism“, leading to the destruction of the classical Roman traditions and eradication of its temples.[73] By the end of the 4th Century, anyone caught worshipping “pagan” gods was executed and their property confiscated.

In 351–2, another Jewish revolt in the Galilee erupted against a corrupt Roman governor.[74] In 362, the last pagan Roman Emperor, Julian the Apostate, announced plans to rebuild the Jewish Temple. He died while fighting the Persians in 363 and the project was discontinued.

In 380 Emperor Theodosius I, the last Emperor of a united Roman Empire, made Christianity the official religion of the Roman Empire.

Byzantine period (390–634)

The Roman Empire split in 390 CE and the region became part of the (Christian) East Roman Empire, known as the Byzantine Empire. Byzantine Christianity was dominated by the (Greek) Eastern Orthodox Church whose massive land ownership has extended into the present. In the 5th century, the Western Roman Empire collapsed leading to Christian migration into the Roman province of Palaestina Prima and development of a Christian majority. Jews numbered 10–15% of the population, concentrated largely in the Galilee. Judaism was the only non-Christian religion tolerated, but restrictions on Jews slowly increased to include a ban on building new places of worship, holding public office or owning Christian slaves. In 425, following the death of the last Nasi, Gamliel VI, the Sanhedrin was officially abolished and the title of Nasi banned. Several Samaritan Revolts erupted in this period,[75] resulting in the decrease of Samaritan community from about a million to a near extinction. Sacred Jewish texts written in Palestine at this time are the Gemara (400), the Jerusalem Talmud (500) and the Passover Haggadah.

In 495 Mar-Zutra II (the Exilarch), set up an independent Jewish city-state in what is now Iraq. It lasted seven years and after its fall, his son Mar-Zutra III moved to Tiberias where he became head of the local religious academy in 520.

The Jewish Menorah, which the Romans took when the temple was destroyed, was reportedly taken to Carthage by the Vandals after the sacking of Rome in 455. According to the Byzantine historian, Procopius, the Byzantine army recovered it in 533 and brought it to Constantinople.[76]

In 611, Khosrow II, ruler of Sassanid Persia invaded the Byzantine Empire. He was helped by Jewish fighters recruited by Benjamin of Tiberias and captured Jerusalem in 614.[77] The “True Cross” was captured by the Persians. The Jewish Himyarite Kingdom in Yemen may also have provided support. Nehemiah ben Hushiel was made governor of Jerusalem. Christian historians of the period claimed the Jews massacred Christians in the city, but there is no archeological evidence of destruction, leading modern historians to question their accounts.[78][79][80] In 628, Kavad II (son of Kosrow), returned Palestine and the True Cross to the Byzantines and signed a peace treaty with them. Following the Byzantine re-entry, Heraclius massacred the Jewish population of Gallilee and Jerusalem and renewed the ban on Jews entering Jerusalem. Benjamin of Tiberias was converted to Christianity.

Early Muslim period (634–1099)

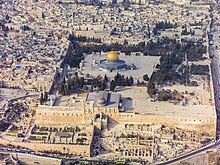

Aerial view of the Temple Mount showing the Dome of the Rock in the center and the al-Aqsa mosque to the south

According to Muslim tradition, on the last night of his life in 620, Muhammed was taken on a journey from Mecca to the “farthest mosque”, whose location many consider to be the Temple Mount, returning the same night.

In about 635, an Arab army led by Muawiyah I conquered Palestine and the entire Levant, making it a province of the new Medina-based Arab Empire. The Byzantine ban on Jews living in Jerusalem came to an end and Palestine gradually came to be dominated politically and socially by Muslims, though the dominant religion of the country down to the Crusades may still have been Christian.[81]

In 661, Muawiyah was crowned Caliph in Jerusalem, becoming the first of the (Damascus-based) Umayyad dynasty. In 691, Umayyad Caliph Abd al-Malik (685–705) constructed the Dome of the Rock shrine on the Temple Mount (where the Jewish temple had been located). A second building, the Al-Aqsa Mosque, was also erected on the Temple Mount in 705. Both buildings were rebuilt in the 10th century following a series of earthquakes.[82] Jews consider the Temple Mount (Muslim name Noble Sanctuary) to contain the Foundation Stone (see also Holy of Holies), which is the holiest site in Judaism. Jews believe it is the site where Abraham tried to sacrifice his son, Isaac, while Muslims believe that Abraham tried to sacrifice his son, Ishmael, in Mecca.

A new city, Ramlah, was built as the Muslim capital of Jund Filastin, (the name given to the province).[83] In 750, Arab discrimination against Non-Arab Muslims led to the Abbasid Revolution and the Umayyads were replaced by the Abbasid Caliphs who built a new city, Baghdad, to be their capital.

During the 8th century, the Caliph Umar II introduced a law requiring Jews and Christians to wear identifying clothing: Jews were required to wear yellow stars round their neck and on their hats. Christians had to wear Blue. Clothing regulations were not always enforced, but did arise during repressive periods and were sometimes designed to humiliate and persecute non-Muslims. A poll tax was imposed on all non-Muslims by all Islamic rulers and failure to pay could result in imprisonment or worse.[84] Non-Muslims were banned from travelling unless they could show a tax receipt. There were also bans on construction of new places of worship and repair of existing places of worship. The system of requiring Jews to wear yellow stars was subsequently adopted also in parts of Christian Europe.

In 982, Caliph Al-Aziz Billah of the Cairo-based Fatimid dynasty conquered the region. The Fatimids were followers of Isma’ilism, a branch of Shia Islam and claimed descent from Fatima, Mohammed’s daughter. Around the year 1,010 the Church of Holy Sepulchre (believed to be Jesus burial site), was destroyed by Fatimid Caliph al-Hakim, who relented ten years later and paid for it to be rebuilt. In 1020 al-Hakim claimed divine status and the newly formed Druze religion gave him the status of a messiah.[82]

Between the 7th and 11th centuries, Jewish scribes, called the Masoretes and located in Galilee and Jerusalem, established the Masoretic Text, the final text of the Hebrew Bible.

Crusades and Mongols (1099–1291)

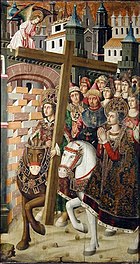

Painting of the siege of Jerusalem during the First Crusade (1099)

In 1099, the First Crusade took Jerusalem and established a Catholic kingdom, known as the Kingdom of Jerusalem. During the conquest, both Muslims and Jews were indiscriminately massacred or sold into slavery.[85] Jews encountered as the Crusaders travelled across Europe were given a choice of conversion or murder, and almost always chose martyrdom. The carnage continued when the Crusaders reached the Holy Land.[86] Ashkenazi orthodox Jews still recite a prayer in memory of the death and destruction caused by the Crusades.

Around 1180, Raynald of Châtillon, ruler of Transjordan, caused increasing conflict with the Ayyubid Sultan Saladin (Salah-al-Din), leading to the defeat of the Crusaders in the 1187 Battle of Hattin (above Tiberias). Saladin was able to peacefully take Jerusalem and conquered most of the former Kingdom of Jerusalem. Saladin’s court physician was Maimonides, a refugee from Almohad (Muslim) persecution in Córdoba, Spain, where all non-Muslim religions had been banned.[87] This was the end of the Golden age of Jewish culture in Spain and Maimonides possessed extensive knowledge of Greek and Arab medicine. His religious writings (in Hebrew and Judeo-Arabic) are still studied by Orthodox Jews. Maimonides was buried in Tiberias. A Crusader city-state at Acre survived for another century.

The Christian world’s response to the loss of Jerusalem came in the Third Crusade of 1190. After lengthy battles and negotiations, Richard the Lionheart and Saladin concluded the Treaty of Jaffa in 1192 whereby Christians were granted free passage to make pilgrimages to the holy sites, while Jerusalem remained under Muslim rule.[88] In 1229, Jerusalem peacefully reverted into Christian control as part of a treaty between Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II and Ayyubid sultan al-Kamil that ended the Sixth Crusade.[89] In 1244, Jerusalem was sacked by the Khwarezmian Tatars who decimated the city’s Christian population, drove out the Jews and razed the city.[90] The Khwarezmians were driven out by the Ayyubids in 1247. In 1258, the Mongols destroyed Baghdad, killing hundreds of thousands. For the next 30 years, the area was the frontier between Mongol invaders (occasional Crusader allies) and the Mamluks of Egypt. The conflict impoverished the country and severely reduced the population. Sultan Qutuz of Egypt eventually defeated the Mongols in the Battle of Ain Jalut (“Goliath’s spring” near Ein Harod), ending the Mongol advances, and his successors eliminated the Crusader states. The last Crusader state, the Kingdom of Acre, fell in 1291, ending the Crusades.

Mamluk period (1291–1517)

The Mamluks ruled Palestine until 1516, regarding it as part of Syria. In Hebron, Baibars banned Jews from worshipping at the Cave of the Patriarchs (the second-holiest site in Judaism); the ban remained in place until its conquest by Israel 700 years later.[91] The Egyptian Mamluk sultan Al-Ashraf Khalil conquered the last outposts of Crusader rule in 1291.

The Mamluks, continuing the policy of the Ayyubids, made the strategic decision to destroy the coastal area and to bring desolation to many of its cities, from Tyre in the north to Gaza in the south. Ports were destroyed and various materials were dumped to make them inoperable. The goal was to prevent attacks from the sea, given the fear of the return of the Crusaders. This had a long-term effect on those areas, which remained sparsely populated for centuries. The activity in that time concentrated more inland.[92]

The collapse of the Crusades was followed by increased persecution and expulsions of Jews in Europe. Expulsions began in England (1290) and were followed by France (1306).[93][94] During the 14th century Jews were blamed for the Black Death in Europe and the communities of Belgium, Holland, Switzerland and Germany were massacred or expelled (Black Death Jewish persecutions). The largest massacres of Jews took place in Spain where some tens of thousands were killed and about half the Jews in the country were forcibly converted. By the end of the 14th century, significant European Jewish communities only existed in Spain, Italy and Eastern Europe.

In January 1492, the last Muslim state was defeated in Spain and six months later the Jews of Spain (the largest community in the world) were required to convert or leave without their property. 100,000 converted with many continuing to secretly practice Judaism, for which the Catholic church’s inquisition (led by Torquemada) now mandated a sentence of death by public burning. 175,000 left Spain.[95] On the day set as the last day for Jews to legally reside in Spain, Columbus sailed to America. In return for a large payment, about 100,000 Spanish Jews were allowed into Portugal, however five years later, their children were seized and they were given the choice of conversion or departing without them.[96] Most converted but continued to practice in secret. The economic success of the converts in Spain and Portugal and suspicion of their sincerity led to laws restricting the rights of Christians of Jewish origin. Escaping Jews were often maltreated by those shipping them and refused entry to various ports around the Mediterranean by communities afraid of being swamped. Expulsions also took place in Italy, affecting survivors of the original expulsion.

Many secret Jews chose to move to the New World, where they were temporarily able to practice Judaism freely (see History of the Jews in Latin America). Other Spanish Jews moved to North Africa, Poland and the Ottoman Empire, especially Thessaloniki (now in Greece) which became the world’s largest Jewish city. Some headed for Israel, which was also controlled by the Ottomans. In Italy, Jews living in Venice were required to live in a ghetto, a practice which spread to the papal states (see Cum nimis absurdum) and was adopted across Catholic Europe. Jews outside the Ghetto often had to wear a yellow star. Secretly practicing Jews could not revert to Judaism inside Europe as this carried a death sentence. The last compulsory Ghetto was administered by the Vatican in Rome and abolished in the 1880s.

In 1523, David Reubeni tried to persuade Emperor Charles V to participate in a plan to raise a Jewish army to conquer Judea and set up a Jewish kingdom, using Jewish warriors from India and Ethiopia. He managed to meet with a number of royal leaders but was eventually executed by the inquisition.

Ottoman period (1516–1917)

Under the Mamluks, the area was a province of Bilad a-Sham (Syria). It was conquered by Turkish Sultan Selim I in 1516–17, becoming a part of the province of Ottoman Syria for the next four centuries, first as the Damascus Eyalet and later as the Syria Vilayet (following the Tanzimat reorganization of 1864).

Old Yishuv

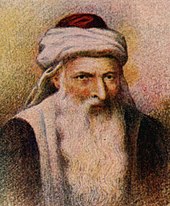

16th-century Safed rabbi Joseph Karo, author of the Jewish law book

The Ottoman Sultans encouraged Jews fleeing the inquisition in Catholic Europe to settle in the Ottoman Empire. Suleiman the Magneficent’s personal physician was Moses Hamon, an inquisition survivor. Jewish businesswomen dominated communication between the Harem and the outside world (see Esther Handali). Between 1535 and 1538 Suleiman the Magnificent (ruled 1520 – 1566) built the current city walls of Jerusalem; Jerusalem had been without walls since the early 13th century. The construction followed the historical outline of the city, but left out a key section of the City of David (today part of Silwan) and what is now known as Mount Zion.

In 1558 Selim II (1566–1574), successor to Suleiman, whose wife Nurbanu Sultan was Jewish,[97] gave control of Tiberias to Doña Gracia Mendes Nasi, one of the richest women in Europe and an escapee from the inquisition. She encouraged Jewish refugees to settle in the area and established a Hebrew printing press. Safed became a centre for study of the Kabbalah. Doña Nasi’s nephew, Joseph Nasi, was made governor of Tiberias and he encouraged Jewish settlement from Italy.[98]

Jewish population was concentrated in Jerusalem, Hebron, Safed and Tiberias, known in Jewish tradition as the Four Holy Cities. Further migration occurred during the Khmelnytsky Uprising in Ukraine, which was accompanied by brutal massacres of tens of thousands of Jews.

In 1660, a Druze revolt led to the destruction of Safed and Tiberias.[99][100] In 1663 Sabbatai Zevi settled in Jerusalem, and was proclaimed as the Jewish messiah by Nathan of Gaza. He acquired a large number of followers before going to Istanbul in 1666, where Sultan Suleiman II forced him to convert to Islam. Many of his followers converted, forming a sect that still exists in Turkey, known as the Dönmeh. In the late 18th century a local Arab sheikh Zahir al-Umar created a de facto independent Emirate in the Galilee. Ottoman attempts to subdue the Sheikh failed, but after Zahir’s death the Ottomans restored their rule in the area.

In 1799 Napoleon briefly occupied the country and planned a proclamation inviting Jews to create a state. The proclamation was shelved following his defeat at Acre.[101] In 1831, Muhammad Ali of Egypt, an Ottoman ruler who left the Empire and tried to modernize Egypt, conquered Ottoman Syria and tried to revive and resettle much of its regions. His conscription policies led to a popular Arab revolt in 1834, resulting in major casualties for the local Arab peasants, and massacres of Christian and Jewish communities by the rebels. Following the revolt, Muhammad Pasha, the son of Muhammad Ali, expelled nearly 10,000 of the local peasants to Egypt, while bringing loyal Egyptian peasants and discharged soldiers to settle the coastline of Ottoman Syria. Northern Jordan Valley was settled by his Sudanese troops.

Jewish workers in Kerem Avraham neighbourhood of Jerusalem (c. 1850s)

In 1838 there was another revolt by the Druze. In 1839 Moses Montefiore met with Muhammed Pasha in Egypt and signed an agreement to establish 100–200 Jewish villages in the Damascus Eyalet of Ottoman Syria,[102] but in 1840 the Egyptians withdrew before the deal was implemented, returning the area to Ottoman governorship. In 1844, Jews constituted the largest population group in Jerusalem. By 1896 Jews constituted an absolute majority in Jerusalem,[103] but the overall population in Palestine was 88% Muslim and 9% Christian.[104]

Birth of Zionism

| Part of a series on |

| Aliyah |

|---|

|

| Jewish return to the Land of Israel |

| Concepts |

| Pre-Modern Aliyah |

| Aliyah in modern times |

| Absorption |

| Organizations |

| Related topics |

During the 19th century, Jews in Western Europe were increasingly granted citizenship and equality before the law; however, in Eastern Europe, they faced growing persecution and legal restrictions, including widespread pogroms in which thousands were murdered, raped or lost their property. Half the world’s Jews lived in the Russian Empire, where they were severely persecuted and restricted to living in the Pale of Settlement. National groups in the Empire, such as the Poles, Lithuanians and Ukrainians were agitating for independence and often regarded the Jews as undesirable aliens. The Jews were usually the only non-Christian minority and spoke a distinct language (Yiddish). An independent Jewish national movement first began to emerge in the Russian Empire and the millions of Jews who were fleeing the country (mostly to United States) carried the seeds of this nationalism wherever they went.

In 1870, an agricultural school, the Mikveh Israel, was founded near Jaffa by the Alliance Israelite Universelle, a French Jewish association. In 1878, “Russian” Jewish emigrants established the village of Petah Tikva, followed by Rishon LeZion in 1882. “Russian” Jews established the Bilu and Hovevei Zion (“Lovers of Zion”) movements to assist settlers and these created communities that, unlike the traditional Ashkenazi-Jewish communities, sought to be economically self-reliant. Existing Ashkenazi-Jewish communities were concentrated in the Four Holy Cities, extremely poor and relied on donations (halukka) from groups abroad. The new settlements were small agricultural communities, heavily funded by the French Baron, Edmond James de Rothschild, who sought to establish economic enterprises. In Jaffa, a vibrant commercial community developed in which Ashkenazi and Sephardi Jews inter-mingled. Many early migrants left due to difficulty finding work. Despite the difficulties, more settlements arose and the community grew.

The new migration was accompanied by a revival of the Hebrew language and attracted Jews of all kinds; religious, secular, nationalists and left-wing socialists. Socialists aimed to reclaim the land by becoming peasants or workers and forming collectives. In Zionist history, the different waves of Jewish settlement are known as “aliyah“. Pogroms in the Dnieper Ukraine of the Russian Empire inspired some of the earliest ideas propagating the idea of emigration to Palestine.[105] After pogroms broke out in 1881, as remedial measures also set new restrictions on Russian Jews, 1.98 million emigrated from the Russian Empire, 1.5 million to the United States and a small number to Palestine, both forming the prospective new centers of Jewish life,[106][107] though there was strong opposition to the latter option.[108] During the First Aliyah, between 1882 and 1903, approximately 35,000 Jews moved to Palestine.[109] After the Ottoman conquest of the central region of their country, from 1881 onwards Yemenite Jews were enabled by new transportation facilities and greater access to knowledge of the outside world, to emigrate to Palestine, often driven by Messianism.[110] By 1890, Jews were a majority in Jerusalem, although the country as a whole was populated mainly by Muslim and Christian Arabs.

In 1896 Theodor Herzl published Der Judenstaat (The Jewish State), in which he asserted that the solution to growing antisemitism in Europe (the so-called “Jewish Question“) was to establish a Jewish state. In 1897, the Zionist Organisation was founded and the First Zionist Congress proclaimed its aim “to establish a home for the Jewish people in Palestine secured under public law.”[111] However, Zionism was regarded with suspicion by the Ottoman rulers and was unable to make major progress.

Between 1904 and 1914, around 40,000 Jews settled in the area now known as Israel (the Second Aliyah). In 1908 the Zionist Organisation set up the Palestine Bureau (also known as the “Eretz Israel Office”) in Jaffa and began to adopt a systematic Jewish settlement policy. Migrants were mainly from Russia (which then included part of Poland), escaping persecution. The first Kibbutz, Degania, was founded by nine Russian socialists in 1909. In 1909 residents of Jaffa established the first entirely Hebrew-speaking city, Ahuzat Bayit (later renamed Tel Aviv). Hebrew newspapers and books were published, Hebrew schools, Jewish political parties and workers organizations were established.

World War I

During World War I, most Jews supported the Germans because they were fighting the Russians who were regarded as the Jews’ main enemy.[112] In Britain, the government sought Jewish support for the war effort for a variety of reasons including an antisemitic perception of “Jewish power” in the Ottoman Empire’s Young Turks movement which was based in Thessaloniki, the most Jewish city in Europe (40% of the 160,000 population were Jewish).[113] The British also hoped to secure American Jewish support for US intervention on Britain’s behalf.

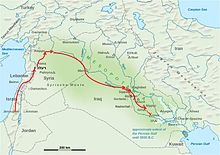

There was already sympathy for the aims of Zionism in the British government, including the Prime Minister Lloyd George.[114] Over 14,000 Jews were expelled by the Ottoman military commander from the Jaffa area in 1914–1915, due to suspicions they were subjects of Russia, an enemy, or Zionists wishing to detach Palestine from the Ottoman Empire,[115] and when the entire population, including Muslims, of both Jaffa and Tel Aviv was subject to an expulsion order in April 1917, the affected Jews could not return until the British conquest. Shortly after the British Army drove the Turks out of Southern Syria,[116] and the British foreign minister, Arthur Balfour, sent a public letter to the British Lord Rothschild, a leading member of his party and leader of the Jewish community. The letter subsequently became known as the Balfour Declaration of 1917. It stated that the British Government “view[ed] with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people”. The declaration provided the British government with a pretext for claiming and governing the country.[117] New Middle Eastern boundaries were decided by an agreement between British and French bureaucrats.

A Jewish Legion composed largely of Zionist volunteers organized by Ze’ev Jabotinsky and Joseph Trumpeldor participated in the British invasion. It also participated in the failed Gallipoli Campaign. The Nili Zionist spy network provided the British with details of Ottoman plans and troop concentrations.[118]

Interregnum (1917–1920)

After pushing out the Ottomans, Palestine came under martial law. The British, French and Arab Occupied Enemy Territory Administration governed the area shortly before the armistice with the Ottomans until the promulgation of the mandate in 1920.

British Mandate of Palestine (1920–1948)

|

This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2021)

|

First years

The British Mandate (in effect, British rule) of Palestine, including the Balfour Declaration, was confirmed by the League of Nations in 1922 and came into effect in 1923. The territory of Transjordan was also covered by the Mandate but under separate rules that excluded it from the Balfour Declaration. Britain signed a treaty with the United States (which did not join the League of Nations) in which the United States endorsed the terms of the Mandate.[119]

The Balfour declaration was published on the 2nd of November 1917 and the Russian revolution took place a week later. The revolution led to civil war in the Russian Empire in which all the participants attacked Jews, who they identified with the Communists. The exception was the Bolsheviks, whose Red Army was commanded by Leon Trotsky whose parents were Jewish (although he rejected all religion). One estimate places the number of pogroms in the Ukraine between 1918 and 1919 at 1,200: figures of those murdered or maimed range upwards of 100,000.[120] Between 1919 and 1923, another 40,000 Jews arrived in Palestine in what is known as the Third Aliyah.[109] Many Greek Jews arrived, mainly from Thessalonika, fleeing the Greco-Turkish War (1919–1922).

Many of the Jewish immigrants of this period were Socialist Zionists and supported the Bolsheviks,[121] who granted Jews equal rights and had many leaders of Jewish origin. The socialist migrants became known as pioneers (halutzim), experienced or trained in agriculture who established self-sustaining communes called Kibbutzim. Malarial marshes in the Jezreel Valley and Hefer Plain were drained and converted to agricultural use. Land was bought by the Jewish National Fund, a Zionist charity that collected money abroad for that purpose. A mainly socialist underground Jewish militia, Haganah (“Defense”), was established to defend outlying Jewish settlements.

The opening ceremony of The Hebrew University of Jerusalem visited by Arthur Balfour, 1 April 1925

After the French victory over the Arab Kingdom of Syria and the Balfour Declaration, clashes between Arabs and Jews took place in Jerusalem during the 1920 Nebi Musa riots and in Jaffa the following year.[122] The Jewish Agency issued the British entry permits and distributed funds donated by Jews abroad.[123] Between 1924 and 1929, over 80,000 Jews arrived in the Fourth Aliyah,[109] fleeing Poland and Hungary, for a variety of reasons: anti-Semitism; in protestation at the heavy tax burdens imposed on trade;[124] and the United States Immigration Act of 1924 which severely limited immigration from Eastern and Southern Europe.[124] The new arrivals were mainly middle-class families who moved into towns and established small businesses and workshops—although lack of economic opportunities meant that approximately a quarter later left. The first electricity generator was built in Tel Aviv in 1923 under the guidance of Pinhas Rutenberg, a former Commissar of St Petersburg in Russia’s pre-Bolshevik Kerensky Government. In 1925 the Jewish Agency established the Hebrew University in Jerusalem and the Technion (technological university) in Haifa. British authorities introduced the Palestine pound (worth 1000 “mils”) in 1927, replacing the Egyptian pound as the unit of currency in the Mandate.[125]

From 1928, the democratically elected Va’ad Leumi (Jewish National Council or JNC) became the main institution of the Palestine Jewish community (Yishuv) and included non-Zionist Jews. As the Yishuv grew, the JNC adopted more government-type functions, such as education, health care and security. With British permission, the Va’ad raised its own taxes[126] and ran independent services for the Jewish population.[127] From 1929 its leadership was elected by Jews from 26 countries.

In 1929 tensions grew over the Kotel (Wailing Wall), the holiest spot in the world for Judaism, a narrow alleyway where the British banned Jews from using chairs or curtains: Many of the worshippers were elderly and needed seats; they also wanted to separate women from men. The Mufti claimed it was Muslim property and deliberately had cattle driven through the alley. He alleged that the Jews were seeking control of the Temple Mount. This (and general animosity) led to the August 1929 Palestine riots. The main victims were the (non-Zionist) ancient Jewish community at Hebron, who were massacred. The riots led to right-wing Zionists establishing their own militia in 1931, the Irgun Tzvai Leumi (National Military Organization, known in Hebrew by its acronym “Etzel”).[128]

Zionist political parties provided private education and health care: the General Zionists, the Mizrahi and the Socialist Zionists, each established independent health and education services and operated sports organizations funded by local taxes, donations and fees (the British administration did not invest in public services[citation needed]).During the interwar period, the perception grew that there was an irreconciliable tension between the two Mandatory functions, of providing for a Jewish homeland in Palestine, and the goal of preparing the country for self-determination.[129] The British rejected the principle of majority rule or any other measure that would give the Arab population, who formed the majority of the population, control over Palestinian territory.[130]

Increase of Jewish immigration

In 1933, the Jewish Agency and the Nazis negotiated the Ha’avara Agreement (transfer agreement), under which 50,000 German Jews would be transferred to Palestine. The Jews’ possessions were confiscated and in return the Nazis allowed the Ha’avara organization to purchase 14 million pounds worth of German goods for export to Palestine and use it to compensate the immigrants. Although many Jews wanted to leave Nazi Germany, the Nazis prevented Jews from taking any money and restricted them to two suitcases so few could pay the British entry tax and many were afraid to leave. The agreement was controversial and the Labour Zionist leader who negotiated the agreement, Haim Arlosoroff, was assassinated in Tel Aviv in 1933. The assassination was used by the British to create tension between the Zionist left and the Zionist right. Arlosoroff had been the boyfriend of Magda Ritschel some years before she married Joseph Goebbels.[131] There has been speculation that he was assassinated by the Nazis to hide the connection but there is no evidence for it.[132]

Between 1929 and 1938, 250,000 Jews arrived in Palestine (Fifth Aliyah). 174,000 arrived between 1933 and 1936, after which the British increasingly prevented immigration, mostly due to the outbreak of the 1936-1939 Arab Revolt. Migrants were mainly from Germany and included professionals, doctors, lawyers and professors. German architects of the Bauhaus school made Tel-Aviv the world’s only city with purely Bauhaus neighbourhoods and Palestine had the highest per-capita percentage of doctors in the world.[citation needed]

Fascist regimes were emerging across Europe and persecution of Jews increased. In many countries (most notably the 1935 German Nuremberg laws), Jews reverted to being non-citizens deprived of civil and economic rights, subject to arbitrary persecution. Significantly antisemitic governments came to power in Poland (the government increasingly boycotted Jews and by 1937 had totally excluded all Jews),[133] Hungary, Romania and the Nazi created states of Croatia and Slovakia, while Germany annexed Austria and the Czech territories.[citation needed]

Arab revolt and the White Paper

Jewish Settlement Police members watching the settlement Nesher during 1936–1939 Arab revolt

Jewish immigration and Nazi propaganda contributed to the large-scale 1936–1939 Arab revolt in Palestine, a largely nationalist uprising directed at ending British rule. The head of the Jewish Agency, Ben-Gurion, responded to the Arab Revolt with a policy of “Havlagah“—self-restraint and a refusal to be provoked by Arab attacks in order to prevent polarization. The Etzel group broke off from the Haganah in opposition to this policy.[citation needed]

The British responded to the revolt with the Peel Commission (1936–37), a public inquiry that recommended that an exclusively Jewish territory be created in the Galilee and western coast (including the population transfer of 225,000 Arabs); the rest becoming an exclusively Arab area. The two main Jewish leaders, Chaim Weizmann and David Ben-Gurion, had convinced the Zionist Congress to approve equivocally the Peel recommendations as a basis for more negotiation.[134][135][136] The plan was rejected outright by the Palestinian Arab leadership and they renewed the revolt, which caused the British to appease the Arabs, and to abandon the plan as unworkable.[137][138]

Testifying before the Peel Commission, Weizmann said “There are in Europe 6,000,000 people … for whom the world is divided into places where they cannot live and places where they cannot enter.”[139] In 1938, the US called an international conference to address the question of the vast numbers of Jews trying to escape Europe. Britain made its attendance contingent on Palestine being kept out of the discussion.[140] No Jewish representatives were invited. The Nazis proposed their own solution: that the Jews of Europe be shipped to Madagascar (the Madagascar Plan). The agreement proved fruitless, and the Jews were stuck in Europe.[citation needed]

With millions of Jews trying to leave Europe and every country in the world closed to Jewish migration, the British decided to close Palestine. The White Paper of 1939, recommended that an independent Palestine, governed jointly by Arabs and Jews, be established within 10 years. The White Paper agreed to allow 75,000 Jewish immigrants into Palestine over the period 1940–44, after which migration would require Arab approval. Both the Arab and Jewish leadership rejected the White Paper. In March 1940 the British High Commissioner for Palestine issued an edict banning Jews from purchasing land in 95% of Palestine. Jews now resorted to illegal immigration: (Aliyah Bet or “Ha’apalah”), often organized by the Mossad Le’aliyah Bet and the Irgun. With no outside help and no countries ready to admit them, very few Jews managed to escape Europe between 1939 and 1945. Those caught by the British were mostly imprisoned in Mauritius.[citation needed]

World War II and the Holocaust

Jewish Brigade headquarters under both Union Flag and Jewish flag

During the Second World War, the Jewish Agency worked to establish a Jewish army that would fight alongside the British forces. Churchill supported the plan but British Military and government opposition led to its rejection. The British demanded that the number of Jewish recruits match the number of Arab recruits,[141] but few Arabs would fight for Britain, and the Palestinian leader, the Mufti of Jerusalem, allied with Nazi Germany.

In June 1940, Italy declared war on the British Commonwealth and sided with Germany. Within a month, Italian planes bombed Tel Aviv and Haifa, inflicting multiple casualties.[142] In May 1941, the Palmach was established to defend the Yishuv against the planned Axis invasion through North Africa. The British refusal to provide arms to the Jews, even when Rommel’s forces were advancing through Egypt in June 1942 (intent on occupying Palestine) and the 1939 White Paper, led to the emergence of a Zionist leadership in Palestine that believed conflict with Britain was inevitable.[143] Despite this, the Jewish Agency called on Palestine’s Jewish youth to volunteer for the British Army (both men and women). 30,000 Palestinian Jews and 12,000 Palestinian Arabs enlisted in the British armed forces during the war.[144][145] In June 1944 the British agreed to create a Jewish Brigade that would fight in Italy.

Approximately 1.5 million Jews around the world served in every branch of the allied armies, mainly in the Soviet and US armies. 200,000 Jews died serving in the Soviet army alone.[146] Many of these war veterans later volunteered to fight for Israel or were active in its support.

A small group (about 200 activists), dedicated to resisting the British administration in Palestine, broke away from the Etzel (which advocated support for Britain during the war) and formed the “Lehi” (Stern Gang), led by Avraham Stern. In 1943, the USSR released the Revisionist Zionist leader Menachem Begin from the Gulag and he went to Palestine, taking command of the Etzel organization with a policy of increased conflict against the British. At about the same time Yitzhak Shamir escaped from the camp in Eritrea where the British were holding Lehi activists without trial, taking command of the Lehi (Stern Gang).

Jews in the Middle East were also affected by the war. Most of North Africa came under Nazi control and many Jews were used as slaves.[147] The 1941 pro-Axis coup in Iraq was accompanied by massacres of Jews. The Jewish Agency put together plans for a last stand in the event of Rommel invading Palestine (the Nazis planned to exterminate Palestine’s Jews).[148]

Between 1939 and 1945, the Nazis, aided by local forces, led systematic efforts to kill every person of Jewish extraction in Europe (The Holocaust), causing the deaths of approximately 6 million Jews. A quarter of those killed were children. The Polish and German Jewish communities, which played an important role in defining the pre-1945 Jewish world, mostly ceased to exist. In the United States and Palestine, Jews of European origin became disconnected from their families and roots. As the Holocaust mainly affected Ashkenazi Jews, Sepharadi and Mizrahi Jews, who had been a minority, became a much more significant factor in the Jewish world. Those Jews who survived in central Europe, were displaced persons (refugees); an Anglo-American Committee of Inquiry, established to examine the Palestine issue, surveyed their ambitions and found that over 95% wanted to migrate to Palestine.[149][150][151]

In the Zionist movement the moderate Pro-British (and British citizen) Weizmann, whose son died flying in the RAF, was undermined by Britain’s anti-Zionist policies.[152] Leadership of the movement passed to the Jewish Agency in Palestine, now led by the anti-British Socialist-Zionist party (Mapai) led by David Ben-Gurion. In the diaspora, US Jews now dominated the Zionist movement.

Illegal Jewish immigration and insurgency

The British Empire was severely weakened by the war. In the Middle East, the war had made Britain conscious of its dependence on Arab oil. British firms controlled Iraqi oil and Britain ruled Kuwait, Bahrain and the Emirates. Shortly after VE Day, the Labour Party won the general election in Britain. Although Labour Party conferences had for years called for the establishment of a Jewish state in Palestine, the Labour government now decided to maintain the 1939 White Paper policies.[153]

Buchenwald survivors arrive in Haifa to be arrested by the British, 15 July 1945

Illegal migration (Aliyah Bet) became the main form of Jewish entry into Palestine. Across Europe Bricha (“flight”), an organization of former partisans and ghetto fighters, smuggled Holocaust survivors from Eastern Europe to Mediterranean ports, where small boats tried to breach the British blockade of Palestine. Meanwhile, Jews from Arab countries began moving into Palestine overland. Despite British efforts to curb immigration, during the 14 years of the Aliyah Bet, over 110,000 Jews entered Palestine. By the end of World War II, the Jewish population of Palestine had increased to 33% of the total population.[154]

In an effort to win independence, Zionists now waged a guerrilla war against the British. The main underground Jewish militia, the Haganah, formed an alliance called the Jewish Resistance Movement with the Etzel and Stern Gang to fight the British. This alliance was dissolved after the King David bombings. In June 1946, following instances of Jewish sabotage, the British launched Operation Agatha, arresting 2,700 Jews, including the leadership of the Jewish Agency, whose headquarters were raided. Those arrested were held without trial.

On 4 July 1946 a massive pogrom in Poland led to a wave of Holocaust survivors fleeing Europe for Palestine. Three weeks later, Irgun bombed the British Military Headquarters of the King David Hotel in Jerusalem, killing 91 people. In the days following the bombing, Tel Aviv was placed under curfew and over 120,000 Jews, nearly 20% of the Jewish population of Palestine, were questioned by the police. In the US, Congress criticized British handling of the situation and considered delaying loans that were vital to British post-war recovery.[155]

Between 1945 and 1948, 100,000–120,000 Jews left Poland. Their departure was largely organized by Zionist activists in Poland under the umbrella of the semi-clandestine organization Berihah (“Flight”).[156] Berihah was also responsible for the organized emigration of Jews from Romania, Hungary, Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia, totalling 250,000 (including Poland) Holocaust survivors. The British imprisoned the Jews trying to enter Palestine in the Atlit detainee camp and Cyprus internment camps. Those held were mainly Holocaust survivors, including large numbers of children and orphans. In response to Cypriot fears that the Jews would never leave (since they lacked a state or documentation) and because the 75,000 quota established by the 1939 White Paper had never been filled, the British allowed the refugees to enter Palestine at a rate of 750 per month.

By 1947 the Labour Government was ready to refer the Palestine problem to the newly created United Nations.

United Nations Partition Plan

On 2 April 1947, the United Kingdom requested that the question of Palestine be handled by the General Assembly.[157] The General Assembly created a committee, United Nations Special Committee on Palestine (UNSCOP), to report on “the question of Palestine”.[158] In July 1947 the UNSCOP visited Palestine and met with Jewish and Zionist delegations. The Arab Higher Committee boycotted the meetings. During the visit the British Foreign Secretary Ernest Bevin ordered that passengers from an Aliyah Bet ship, SS Exodus 1947, to be sent back to Europe. The Holocaust surviving migrants on the ship were forcibly removed by British troops at Hamburg, Germany.

The principal non-Zionist Orthodox Jewish (or Haredi) party, Agudat Israel, recommended to UNSCOP that a Jewish state be set up after reaching a religious status quo agreement with Ben-Gurion regarding the future Jewish state. The agreement granted an exemption from military service to a quota of yeshiva (religious seminary) students and to all orthodox women, made the Sabbath the national weekend, guaranteed Kosher food in government institutions and allowed Orthodox Jews to maintain a separate education system.[159]

The majority report of UNSCOP proposed[160] “an independent Arab State, an independent Jewish State, and the City of Jerusalem”, the last to be under “an International Trusteeship System”.[161] On 29 November 1947, in Resolution 181 (II), the General Assembly adopted the majority report of UNSCOP, but with slight modifications.[162] The Plan also called for the British to allow “substantial” Jewish migration by 1 February 1948.[163]

Neither Britain nor the UN Security Council took any action to implement the recommendation made by the resolution and Britain continued detaining Jews attempting to enter Palestine. Concerned that partition would severely damage Anglo-Arab relations, Britain denied UN representatives access to Palestine during the period between the adoption of Resolution 181 (II) and the termination of the British Mandate.[164] The British withdrawal was finally completed in May 1948. However, Britain continued to hold (formerly illegal) Jewish immigrants of “fighting age” and their families on Cyprus until March 1949.[165]

Civil War

The General Assembly’s vote caused joy in the Jewish community and discontent among the Arab community. Violence broke out between the sides, escalating into civil war. From January 1948, operations became increasingly militarized, with the intervention of a number of Arab Liberation Army regiments inside Palestine, each active in a variety of distinct sectors around the different coastal towns. They consolidated their presence in Galilee and Samaria.[166] Abd al-Qadir al-Husayni came from Egypt with several hundred men of the Army of the Holy War. Having recruited a few thousand volunteers, he organized the blockade of the 100,000 Jewish residents of Jerusalem.[167] The Yishuv tried to supply the city using convoys of up to 100 armoured vehicles, but largely failed. By March, almost all Haganah‘s armoured vehicles had been destroyed, the blockade was in full operation, and hundreds of Haganah members who had tried to bring supplies into the city were killed.[168]

Up to 100,000 Arabs, from the urban upper and middle classes in Haifa, Jaffa and Jerusalem, or Jewish-dominated areas, evacuated abroad or to Arab centres eastwards.[169] This situation caused the US to withdraw their support for the Partition plan, thus encouraging the Arab League to believe that the Palestinian Arabs, reinforced by the Arab Liberation Army, could put an end to the plan for partition. The British, on the other hand, decided on 7 February 1948 to support the annexation of the Arab part of Palestine by Transjordan.[170] The Jordanian army was commanded by the British.

David Ben-Gurion proclaiming the Israeli Declaration of Independence in 1948

David Ben-Gurion reorganized the Haganah and made conscription obligatory. Every Jewish man and woman in the country had to receive military training. Thanks to funds raised by Golda Meir from sympathisers in the United States, and Stalin’s decision to support the Zionist cause, the Jewish representatives of Palestine were able to purchase important arms in Eastern Europe.

Ben-Gurion gave Yigael Yadin the responsibility to plan for the announced intervention of the Arab states. The result of his analysis was Plan Dalet, in which Haganah passed from the defensive to the offensive. The plan sought to establish Jewish territorial continuity by conquering mixed zones. Tiberias, Haifa, Safed, Beisan, Jaffa and Acre fell, resulting in the flight of more than 250,000 Palestinian Arabs.[171] The situation was one of the catalysts for the intervention of neighbouring Arab states.

On 14 May 1948, on the day the last British forces left from Haifa, the Jewish People’s Council gathered at the Tel Aviv Museum and proclaimed the establishment of a Jewish state in Eretz Israel, to be known as the State of Israel.[172]

State of Israel (1948–present)

War of Independence

Avraham Adan raising the Ink Flag marking the end of the 1948 Arab–Israeli War

Immediately following the declaration of the new state, both superpower leaders, US President Harry S. Truman and Soviet leader Joseph Stalin, recognized the new state.[173] The Arab League members Egypt, Transjordan, Syria, Lebanon and Iraq refused to accept the UN partition plan and proclaimed the right of self-determination for the Arabs across the whole of Palestine. The Arab states marched their forces into what had, until the previous day, been the British Mandate for Palestine, starting the first Arab–Israeli War. The Arab states had heavy military equipment at their disposal and were initially on the offensive (the Jewish forces were not a state before 15 May and could not buy heavy arms). On 29 May 1948, the British initiated United Nations Security Council Resolution 50 declaring an arms embargo on the region. Czechoslovakia violated the resolution, supplying the Jewish state with critical military hardware to match the (mainly British) heavy equipment and planes already owned by the invading Arab states. On 11 June, a month-long UN truce was put into effect.

Following independence, the Haganah became the Israel Defense Forces (IDF). The Palmach, Etzel and Lehi were required to cease independent operations and join the IDF. During the ceasefire, Etzel attempted to bring in a private arms shipment aboard a ship called “Altalena“. When they refused to hand the arms to the government, Ben-Gurion ordered that the ship be sunk. Several Etzel members were killed in the fighting.

Large numbers of Jewish immigrants, many of them World War II veterans and Holocaust survivors, now began arriving in the new state of Israel, and many joined the IDF.[174]

After an initial loss of territory by the Jewish state and its occupation by the Arab armies, from July the tide gradually turned in the Israelis’ favour and they pushed the Arab armies out and conquered some of the territory that had been included in the proposed Arab state. At the end of November, tenuous local ceasefires were arranged between the Israelis, Syrians and Lebanese. On 1 December King Abdullah announced the union of Transjordan with Arab Palestine west of the Jordan; only Britain recognized the annexation.

Armistice Agreements

Israel signed armistices with Egypt (24 February), Lebanon (23 March), Jordan (3 April) and Syria (20 July). No actual peace agreements were signed. With permanent ceasefire coming into effect, Israel’s new borders, later known as the Green Line, were established. These borders were not recognized by the Arab states as international boundaries.[175] Israel was in control of the Galilee, Jezreel Valley, West Jerusalem, the coastal plain and the Negev. The Syrians remained in control of a strip of territory along the Sea of Galilee originally allocated to the Jewish state, the Lebanese occupied a tiny area at Rosh Hanikra, and the Egyptians retained the Gaza strip and still had some forces surrounded inside Israeli territory. Jordanian forces remained in the West Bank, where the British had stationed them before the war. Jordan annexed the areas it occupied while Egypt kept Gaza as an occupied zone.

Following the ceasefire declaration, Britain released over 2,000 Jewish detainees it was still holding in Cyprus and recognized the state of Israel. On 11 May 1949, Israel was admitted as a member of the United Nations.[176] Out of an Israeli population of 650,000, some 6,000 men and women were killed in the fighting, including 4,000 soldiers in the IDF (approximately 1% of the population). According to United Nations figures, 726,000 Palestinians had fled or were expelled by the Israelis between 1947 and 1949.[177] Except in Jordan, the Palestinian refugees were settled in large refugee camps in poor, overcrowded conditions and denied citizenship by their host countries. In December 1949, the UN (in response to a British proposal) established an agency (UNRWA) to provide aid to the Palestinian refugees. It became the largest single UN agency and is the only UN agency that serves a single people.

A 120-seat parliament, the Knesset, met first in Tel Aviv then moved to Jerusalem after the 1949 ceasefire. In January 1949, Israel held its first elections. The Socialist-Zionist parties Mapai and Mapam won the most seats (46 and 19 respectively). Mapai’s leader, David Ben-Gurion, was appointed Prime Minister, he formed a coalition which did not include Mapam who were Stalinist and loyal to the USSR (another Stalinist party, non-Zionist Maki won 4 seats). This was a significant decision, as it signaled that Israel would not be in the Soviet bloc. The Knesset elected Chaim Weizmann as the first (largely ceremonial) President of Israel. Hebrew and Arabic were made the official languages of the new state. All governments have been coalitions—no party has ever won a majority in the Knesset. From 1948 until 1977 all governments were led by Mapai and the Alignment, predecessors of the Labour Party. In those years Labour Zionists, initially led by David Ben-Gurion, dominated Israeli politics and the economy was run on primarily socialist lines.

Within three years (1948 to 1951), immigration doubled the Jewish population of Israel and left an indelible imprint on Israeli society.[178][179] Overall, 700,000 Jews settled in Israel during this period.[180] Some 300,000 arrived from Asian and North African nations as part of the Jewish exodus from Arab and Muslim countries.[181] Among them, the largest group (over 100,000) was from Iraq. The rest of the immigrants were from Europe, including more than 270,000 who came from Eastern Europe,[182] mainly Romania and Poland (over 100,000 each). Nearly all the Jewish immigrants could be described as refugees, however only 136,000 who immigrated to Israel from Central Europe, had international certification because they belonged to the 250,000 Jews registered by the allies as displaced after World War II and living in displaced persons camps in Germany, Austria and Italy.[183]

In 1950 the Knesset passed the Law of Return, which granted to all Jews and those of Jewish ancestry (Jewish grandparent), and their spouses, the right to settle in Israel and gain citizenship. That year, 50,000 Yemenite Jews (99%) were secretly flown to Israel. In 1951 Iraqi Jews were granted temporary permission to leave the country and 120,000 (over 90%) opted to move to Israel. Jews also fled from Lebanon, Syria and Egypt. By the late sixties, about 500,000 Jews had left Algeria, Morocco and Tunisia. Over the course of twenty years, some 850,000 Jews from Arab countries (99%) relocated to Israel (680,000), France and the Americas.[184][185] The land and property left behind by the Jews (much of it in Arab city centres) is still a matter of some dispute. Today there are about 9,000 Jews living in Arab states, of whom 75% live in Morocco and 15% in Tunisia. Vast assets, approximately $150 billion worth of goods and property (before inflation) were left behind in these countries.[186][187]

Menachem Begin addressing a mass demonstration in Tel Aviv against negotiations with Germany in 1952